Run

Lola Run

by Tom Whalen

Film Quarterly, Vol.53, No.3 (Spring 2000), 33-40.

Director/writer: Tom Tykwer. Producer: Stefan Arndt.

Cinematographer:

Frank Griebe. Editor: Mathilde Bonnefoy.

Sony Pictures Classics.

Tom Tykwer's Run Lola Run (Lola rennt, 1998) blasts open doors for viewers in the late 90s the way Godard's Breathless (1959) did for viewers in the late 50s. In few other ways would I compare these two films. Godard's exercise is tinted cool, hip, his characters posturing cartoons; whereas Tykwer's is hot, kinetic, and his (at times animated) characters bristling realities. Though a profoundly philosophical and German film, Run Lola Run leaps lightly over the typical Teutonic metaphysical mountains. Tykwer's work doesn't have the Romantic receptive gaze of a Wenders or entertain the grapple with the gods of a Herzog, but instead possesses a ludic spirit willing to see life and art as a game. Nor, though as excited by the techniques of cinema as the film of a first-time director (Run Lola Run is Tykwer's eighth movie), is it the loose, dehumanized display of, say, Pulp Fiction (1994) or Trainspotting (1996). Run Lola Run is fast, but never loose. It's as tightly wound and playful as a Tinguely machine and constructed with care.

What are the constituent components of this energized mechanism? This essay proposes that the film's unifying principle is the Game; its unifying theme, Time and determinism; its dominant formal principle, the Dialectic; and its (subsidiary) narrative systems those of the love story and fairy tale. By examining each of these areas and related motifs, I hope to illuminate at least some of the rules of Tom Tykwer's game.1

I. THE GAME

As long as I can play the game,

I can play it, and everything is all right.

—Ludwig Wittgenstein

Of the films two epigraphs (the first by T. S. Eliot and the second by S. Herberger), the one that concerns me at the moment is the second: "Nach dem Spiel ist [end of p.33]vor dem Spiel." "After the game is before the game." Or: When one game ends, another is about to begin. Hardly a pause, and even the pause is preparation for the next game. What dominates, whether before or after the game, is the game itself. So whatever else this epigraph might mean (and who might S. Herberger be? A German soccer coach, natürlich), it reminds us that while watching Run Lola Run we should never forget that we are in a sense watching a game. Or in several senses.

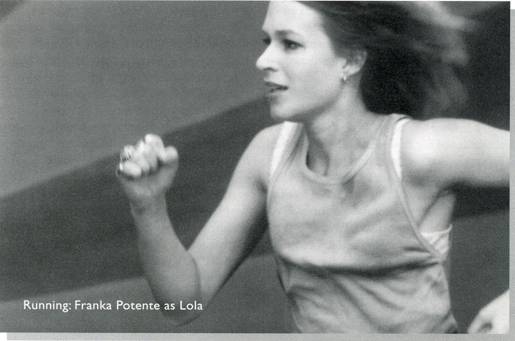

Games, like films, are usually time-bound, and Lola (Franka Potente) is a most time-bound character: she has 20 minutes to come up with 100,000 Deutschmarks in order to save the life of her boyfriend Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu). Games can also be played again; if you lose one game, you can always try again. So if film is like a game, then why not give Lola a second chance to win, or a third? "The space-time continuum is unhinged, so what?" Tykwer said in an interview, "We're at the movies!" ("Das Raum-Zeit-Kontinuum wird aus den Angeln gehoben, na und? Wir sind doch im Kino!") (Tykwer, 137).

Run

Lola Run's film antecedent might well be the short Same Player Shoots Again (1967) by Wim

Wenders. "For me," Wenders has said of this abstract

"thriller" which basically repeats a single two-minute shot five

times, "it had a lot to do with pinball machines. . . . Visually, it's as

if you had five balls. In fact, that was the idea, to edit it this way" (

Two further thoughts: 1) Games exist, as much as possible, in a zone of safety. Like Wile E. Coyote, a game character can't (or shouldn't) be harmed. No one dies in Run Lola Run. 2) The player should be able to affect the outcome of the game. Lola is determined, beyond all logic (so determined that she rises above the logically possible), to win the game. But can a player affect the outcome even of a game of chance such as roulette? Yes, in this case especially roulette.

What is important while viewing Run Lola Run is to acknowledge the director's central conceit of life/art/film as a game. In the opening sequence, after the epigraphs, Tykwer again emphasizes the point. A clock's pendulum swings ominously back and forth across the screen. The camera tilts upwards, rises, and we plunge into a gaping black hole of Chronos's mouth. Swallowed by time, we are presented with a handful of characters, zoom-selected, like playing cards, from a crowd of figures. Then a man in a guard's uniform (Armin Rohde) holding a soccer ball tells us: "Ball is round, game lasts 90 minutes. That much is clear. Everything else is theory." ("Ball is rund, Spiel dauert 90 Minuten. Soviel is schon ma klar. Allet andere is Theorie" [Tykwer, 7].) And then he says, "Und ab!" ("Go!"), kicking the ball high into the air and the camera soars up with it, while below the figures coalesce into the words LOLA RENNT.

II. TIME

Time is the substance I am

made of.

—Jorge Luis Borges

Then the camera plunges back down toward the lone figure of the guard standing just inside the "O" of LOLA and then into the "O" tunnel of the animated credit sequence. How to escape this "O," the closed circle of time, is Lola's metaphysical problem. Tykwer's assessment that Run Lola Run is "an action film that carries a philosophical idea, woven in very playfully, however, not placed in the center" (130) masks the foregrounding of time in the narrative and its use as a frequent visual motif. Clocks, for example, are everywhere: from the film's first sound (the ticking of a clock), to the clock that swallows our gaze in the opening, to the three clocks in the animated credit sequence, to the "O" in LOLA, to the cross-cutting from Lola as she runs to meet Manni, to the clock Manni watches as he waits to see if Lola will arrive before the 20 minutes are up. We [end of p.34]can't ignore Lola's temporal prison. So conscious is the film of time that several of its images serve as visual metaphors of clocks: an overhead shot of Lola running across a square (Round One) makes a circular fountain look like a clock; another overhead (Round Two), of Manni lying on the pavement after an ambulance has run over him, positions him as if his limbs were the hands of a clock.

Perhaps it's for the best that, while she stands in her room talking to Manni on the phone, Lola doesn't notice the tortoise walking past her left foot and thus misses this comic reference to Zeno's second paradox, which, as quoted "more or less in Zeno's words" in A Newcomer's Guide to the Afterlife, reads:

Achilles must first

reach the place from which the tortoise started. By that time the tortoise will

have got on a little way. Achilles must then traverse that, and still the tortoise

will be ahead. Achilles is always coming nearer, but he never makes up to it.

(99)

Had she been aware that the tortoise gets a head start on her, she might never have even attempted to reach Manni.

The animated running Lola of the credit sequence punches and shatters clocks one and two, but is swallowed up by clock three. But Lola's shattering of the clocks does foreshadow her developing powers as she becomes more and more aware of her situation—that she is literally repeating, with variations, her 20-minute rounds. To this extent, Run Lola Run is a coming-of-age story, albeit a fast-track one, wherein Lola moves from dependence on her parents to independence, from ignorance (powerlessness) to knowledge (power) of her player status in the game universe. "We shall not cease from exploration," reads the film's first epigraph, from T.S. Eliot's "Little Gidding," "And the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time." The circling back and back again to her problem's beginning allows Lola to "know the place," to understand her situation.

Two examples of how Lola learns from round to round should suffice: 1) Lola, in the animated sequence we move into on her mother's television, runs (Round One) past a dog and a punk kid hanging out on the landing; in Round Two the dog growls and the kid trips her, sending Lola sprawling down the stairs; in Round Three, Lola leaps over the growling dog and astonished kid, then growls back at the dog who whimpers in fright. 2) In Round One Lola runs parallel with then past an ambulance when it skids to a stop in front of a sheet of glass being carried across the street; running alongside the ambulance in Round Two, Lola asks the driver if he can take her, and, distracted, the driver crashes the ambulance through the glass (and shortly after this, he will run over Manni); by Round Three, a wiser Lola, when the ambulance skids to a stop in front of the glass, takes the opportunity to hop into the back, where she will take the hand of a heart attack victim and bring him back to life. (Pointing out that Lola seems to learn things from one round to the next, Tykwer said: "Logically speaking it's impossible, of course—but to secretly play down such elements is the beauty of film" [137]).

If Lola could stop time (and she can, but doesn't know it yet), she would. In her father's bank office (Round One), frustrated with his unwillingness to help her and learning that her "Papa" (Herbert Knaup) is having an affair with a woman (Nina Petri) who also works in the bank, Lola screams, shattering the clock on the wall and stopping for a moment, at least figuratively, her tormentor. Earlier she has screamed at Manni on the phone in order to shut him up, and the bottles on her TV break. But it is the third scream, in the casino at the roulette wheel, shot in a tight close-up (a visual shout), that is truly efficacious and fantastic. This time, besides shattering the drinking glasses on the sideboards and in the guests' hands, her scream is the manifestation of her immanent will which causes the ball rolling around in the wheel to rest finally on 20, the number, of course, of Lola's game—the temporal condition placed on her saving Manni's life and her bet.

The roulette wheel is another image of Lola's temporal circling. Lola herself, long before we enter the casino, seems to be in the middle of a wheel when she turns round and round as the faces of people she considers asking for the DM 100,000 appear before her, among them her father, who shakes his head "No," and an animated figure (later we'll recognize him as the live-action croupier [Klaus Muller] in the casino), who says, "Rien ne va plus" ("No more bets"). In one frame, Lola runs past a wall with a roulette wheel's spoke-like pattern, suggesting Lola is less player at this moment than she is the ball put into play (or is she the wheel's axis?). But the movement of a roulette ball isn't altogether circular. The ball moves clockwise to the wheel's counterclockwise motion, and the friction this creates causes it eventually to fall into the wheel's bowl. Thus, with a little opposition, a dialectical nudge, the circle becomes a spiral, and the spiral, as Vladimir Nabokov knew, "is a spiritualized circle. In the spiral form, the circle, uncoiled, unwound, has ceased to be vicious; it has been set free" (275).

[end of p.35]

III. THE DIALECTIC

I thought this up when I was a schoolboy,

and I also discovered that Hegel's triadic series

(so popular in old

merely the essential spirality of all things

in their relation to time.

—Vladimir Nabokov

This dialectical shift from circle to spiral is visually represented in the sign for a nightclub, Die Spirale, that spirals (like an imploding clock) behind Manni on the corner where he phones Lola. The image is also seen in the animated tunnel/spiral in the credit sequence, and in several camera movements: around Manni and Lola when they are surrounded by the police; in the 180 [degrees] turn/reverse turn around Manni and the bum (Joachim Krol) who has Manni's money bag; around Lola's mother (Ute Lubosch) before we enter the animated image on television of Lola running down the (spiral) staircase. We even see a spiral pattern on Manni and Lola's pillows in the "transitional" between-life-and-death scenes of our two characters in bed. These spirals remind us that Lola's journey is not essentially circular. Time for Lola (and for us) is not circular, but (dialectically) spiral.

On the narrative level, the tripartite structure functions as the film's fulcrum. In Round One (thesis) Lola dies; in Round Two (antithesis) Manni dies; in Round Three (synthesis) both live. In Round One Manni holds up a Bolle supermarket; in Round Two Lola holds up her father's bank; in Round Three both get lucky: Lola wins DM 100,000 at the casino and Manni recovers the DM 100,000 the bum picked up when Manni accidentally left his bag on the subway.

Other significant (and seemingly insignificant) events deviate from round to round.

Lola and Papa

I: Lola's father agrees to marry his mistress, rejects Lola's plea for help, and shoves her out of the bank; II: Lola's father learns from his mistress he is not the progenitor of her pregnancy, and Lola steals the guard's gun and forces Papa at gun point to tell the bank teller (Lars Rudolph) to give her the money; III: Lola arrives at the bank too late; Papa has already left with Herr Meier (Ludger Pistor).

Lola and Herr Meier

I: Lola runs past a car leaving a driveway; distracted by Lola, the driver does not see the oncoming car containing Ronnie (Heino Forch), the drag dealer for whom Manni made the drop and pick-up, and his two musclemen, and Ronnie's car slams into the driver's; II: Lola jumps onto and across the hood of the car leaving the driveway; distracted, the driver (we still don't know he's Herr Meier) slams into Ronnie's oncoming car; III: Lola lands on the hood of Herr Meier's car, recognizes him, and he her; Herr Meier asks, "Lola, alles in Ordnung?" ("Lola, is everything O.K.?"), and Lola says "No," while Ronnie's car passes unharmed (for the moment—later in Round Three the two cars will be in an accident).

Lola and the bad-tempered woman with the baby carriage

I: Lola almost runs into a bad-tempered woman (Julia Lindig) with a baby carriage, who shouts after Lola, "Watch where you're going, you slut!" ("Paß doch auf du Schlampe!"); II: Lola almost runs into the bad-tempered woman with a baby carriage who shouts after Lola: "Hey! Watch out, you stupid cow!" ("Mensch! Augen auf, du blöde Kuh!") and adds, "Kackschlampe!" ("Fucking bitch!"). III: Lola misses her entirely, and the bad-tempered woman just hisses after her but says nothing.

Lola and the bum

I: Lola brushes past the bum carrying Manni's drug money bag; II: Lola bumps straight into him, but again has no idea he holds the (or one) solution to her dilemma; III: Lola doesn't encounter the bum at all, because he has bought a bicycle from . . .

Lola and the bicycler

I: Running parallel with a bicycler (Sebastian Schipper), Lola is offered the bike for DM 50, declines, and runs up the steps of a bridge; II: again, Lola is asked if she needs a bicycle and is offered it for DM 50, and the bicycler adds that it's "like new," but Lola says, "It's stolen!" (perhaps a true insight or she's recalling what made her miss her appointment with Manni in the first place, and thus the event that sets the dominoes of this tale tumbling: the theft of her Moped), and the bicycler pedals past her. (Lola's Moped and its thief will also be involved in the [third] accident between Herr Meier's and Ronnie's cars.); III: running onto the street to avoid the group of nuns she has in the previous rounds run through, she bumps into the bicycler, apologizes, runs on, and the biker tuns off to an Imbiss kiosk where he sells the bum the bicycle, which causes Lola not to encounter him in this round, but allows Manni later to see him and chase him down.

[end of p.36]

Like a pinball, the characters (objects) in Run Lola Run carom crazily from cushion to knob to flipper to (ding! ding!) post, and from round to round no character follows the exact same pattern. Each contact effects changes in all that follow (like the "run" of the stacked dominoes falling that we see on Lola's TV when she is talking to Manni on the phone in the narrative's opening), but the points of (present or absent) contact (chronologically: Lola's mother on the phone, the animated Lola and punk kid with dog, Lola and the bad-tempered woman with the baby carriage, Lola and Herr Meier, Lola and the nuns, Lola and the bicycler, Lola and the bum, Lola and the bank guard, Lola and Papa, Lola and the old woman in front of the bank she asks for the time, Lola and the ambulance, Lola and Manni) never change.

That cause and effect (the smallest cause producing a great consequence) is definitely on Tykwer's mind is clear if we consider some of the film's rapid-fire flash forwards. "UND DANN" ("AND THEN") these sequences begin, and what follows is a series of still frames accompanied by the shutter click and whir of a still camera that reveals a minor character's future. The three futures of the bad-tempered woman are, from round to round: 1) She becomes a social welfare case, loses her child, steals another in a park while the father is taking a piss in the bushes, and is last seen being chased by the father and two other people; 2) she buys a Lotto ticket and wins, purchases a new car, is last seen in a lounge chair beside her baby in a crib as she and her husband share a toast in the front yard of her new home; 3) she encounters a Jehovah's Witness on the street, prays in a church, her husband takes communion, and she is last seen with another woman on the street offering copies of Jehovah's Witness publications Erwachet! (Awake) and Wachturm (Watchtower).

As chaos theory attests, the slightest variation can produce enormous changes for the characters. After Lola runs past the bicycler in Round One, his first future finds him chased and beaten up by hard rockers; then, his face still bruised and bloodied, he buys a meal in a cafeteria, is befriended by the cashier, and the two of them are last seen in their wedding clothes as they leave their wedding. In Round Two, now a bum with a beard, he begs in front of a supermarket, begs in the subway, blathers to a woman on a bench in the forest, and is last seen as a junkie passed out in a WC. In Round Three, when Lola leaves him, instead of a flash forward, the image shifts to video (this occurs whenever Lola or Manni are not in a scene), and we follow him to the Imbiss where he meets the bum with Manni's money who will buy his bicycle, which means Lola will not encounter him in Round Three, but Manni will. "Twirl follows twirl," Nabokov says, "and every synthesis is the thesis of the next series" (275). (Although I am using the term "dialectic," as does Nabokov, in a rather loose sense, a more rigorous Hegelian approach could be applied to Run Lola Run: the antithesis [Round Two] does negate the thesis [Round One], and the synthesis [Round Three] incorporates both, allowing Lola to land with a new, hard-won knowledge of her basic ontological ground, not "Being" as such but at least "Becoming," which, as Hegel said, "is the first adequate vehicle of truth" [122].)

The dialectic also generates much of the film's visual multiplicity. Tykwer's use of the split screen exemplifies Run Lola Run's dialectical strategy. In frame left, Manni outside the Bolle awaits Lola; in frame right, Lola runs desperately toward Manni, their faces almost touching in cinematic but not narrative space; then from bottom frame arises, up to Manni and Lola's necks, the top arc of the supermarket's clock as the second hand ticks to 12. In another split screen, we see frame left Manni foregrounded and Lola backgrounded, and frame right Lola foregrounded and Manni backgrounded—an example, one might say, of a simultaneous shot/reverse shot. The simultaneous dialectical move is also shown when Lola's image is wiped to the right while the Bolle's automatic door opens to the left.

The possibilities generated by Run Lola Run's dialectical drive, its oppositional play, links with the film's theme of "the possibilities of life." As Tykwer told his interviewer:

A film about the possibilities of life, it was clear, needed to be a film about the possibilities of cinema as well. That's why there are different formats in Run Lola Run; there is color and black and white, slow motion and speeded-up motion, all elementary building blocks that have been used for ages in film history. George Melies was already able to work with these effects, especially with double exposure and tricks. . . . Animation suggests: anything can happen in any given moment, and that gives the film additional power (131).

Black and white is used for Lola and Manni's memory sequences, when Lola remembers the theft of her Moped and Manni recalls how he lost the drug money. The animated moments are in the credit sequence, Lola running out of the apartment (first seen on her mother's television), and the single shot of the croupier saying "Rien ne va plus." Video, as stated before, only occurs in those sequences which neither Lola nor Manni [end of p.37] witness directly, but which fill in the narrative, for example the bum picking up the bag on the subway, Papa and his mistress in his bank office together before Lola arrives, and when the bicycler meets the bum at the kiosk.

"Run Lola Run is a movie about the possibilities of the world, of life, and of cinema," Tykwer told his crew (117). Tykwer's ludic sensibility shapes the film's formal qualities (the aesthetic rules of the game), as well as informing the film's themes: of time, determinism, and possibility. The dialectical play helps keep it all alive. And what is the life possibility driving the film's basic narrative? Well, love, of course, as in any typical Hegelian movie romance.

IV. LOVE STORY

I shall have to say, for example, that there is

on the one hand a multiplicity

of successive states of consciousness,

and on the other a unity

which binds them together.

—Henri Bergson

Lola loves Manni. That much is clear.

Lola minus Manni makes no sense. Lola plus Manni is what matters. "I'm a

part of you, dear," are the lyrics we hear when Lola is shot at the end of

Round One; "My lonely nights are through, dear, since you said you were

mine." Aren't the sentiments expressed here in part what brings Lola out

of death, allowing her to begin her game again? Tykwer's "

And it is Lola, we must remember, who is the driving force here; Lola runs, whereas Manni is more often than not stationary. Lola is the player who must counteract the deterministic forces set against her winning the game. Still, these two are a pair, emotionally and visually. Thus the split frames that put them side by side and the liminal, between-life-and-death scenes that find them in bed together. There are even subtle, complex, near match-cuts of the two of them: In an overhead shot, Lola in frame left runs diagonally up left across a square in a grid pattern with a fountain (circle/clock/wheel) frame right. Cut to: a low angle shot of Manni frame left in the phone booth with its grid pattern and frame right the large spiral of the club Die Spirale. Thus, shots A/B: Lola/Manni to the left; circle/spiral to the right (circle to spiral in one stroke!). This from Round One. In Round Two, Tykwer changes the angle, but not the connection. In the overhead shot, Lola runs across the square, but the fountain is out of the frame and the square's grid is at a diagonal—Lola runs parallel with the gridline, not against it. Cut to: Manni in the phone booth shot at a low angle with the phone booth's grid in the same diagonal as the square's grid, and the spiral is out of the frame.2

Another dialectical conjoining of Lola and Manni occurs when Lola helps Manni rob the Bolle by knocking down the security guard. His gun slides (like a hockey puck) to Manni's feet (ß), and Manni shuffles it back to Lola (à). In the transitional universe we slip into after each lover "dies," Manni and Lola are lying side by side. We see them only from their shoulders up lying on their pillows with their spiral patterns. After Lola's "death," she lies on Manni's arm; after Manni's "death," he lies on Lola's arm.

Lola's passion (it's never overtly a sexual passion, but one of love) and the film's manifest themselves, as I've already suggested, in the narrative and the multiplicity of cinematic techniques (animation, video, black and white, jump cuts, slow motion, rapid and sometimes collisive montage, Lola running in one direction dissolving into Lola running in another direction), but one could say the key emblem for this mercurial, exhilarating film's passion is the color red. Lola's phone is red and so is the bag with money. A red ambulance runs over Manni. A red light is foregrounded, a red car passes by. Red arrows on a wall point Lola in the direction she's running. The Bolle sign is red. Fades to red occur when Lola and Manni, respectively, die and enter a liminal zone shot with a red filter. And, of course, Lola's hair is red. A bright, dyed red, the film's visual lifeblood threading its way through this 24-frames-per-second labyrinth. "I wish I were a heartbeat/That never comes to rest," sings the voice of Franka Potente (Lola) during Lola's third and, at last, successful run.

At the end of the second round, when Lola appears before Manni can rob the supermarket, Manni looks lovingly at her, crosses the street, and gets run over by the ambulance. These two lovers only have eyes for each other. One would think that this would have been enough to keep at bay the critics who saw in the film's stylistic display and speed an anti-humanistic element. Janet Maslin, in her New York Times review (March 26, 1999), after praising the film as "playfully profound," continued her "praise" by calling Run Lola Run "post-[end of p.38]human"—hardly an accurate term for the human moments evident in the desires and dilemmas of the characters (all the characters) and the director's aesthetic (humanistic) vision. Which is not to say that Run Lola Run is a realistic, in-depth, psychological character study; fairy tales never are.

V. FAIRY TALE

Play only becomes

possible, thinkable

and understandable when an influx of mind

breaks down the absolute determinism

of the cosmos.

—Johan Huizinga

For what is Run Lola Run if not a fairy tale, albeit of the self-conscious, philosophical variety. The film itself is clearly aware of its fairy tale status. Its tripartite structure is the same structural (and magical) three that underlies so many traditional fairy tales. In her "Wish" song, Lola sings "I wish I were a princess/With armies at her hand/I wish I were a ruler/Who'd make them understand." Lola is our princess and Manni our prince, though the genders, as is appropriate for the late 1990s (in the sense that the princess must save the prince), are reversed. True, these two are not your usual figures of royalty, but then neither at first were Aschenbrödel and Schneewittchen (Cinderella and Snow White). Lola's father isn't a stand-up papa (and possibly, according to what he tells her in Round One, he isn't even her real father), and her mother's an astrologically fixated drunk. But the bank guard Schuster recognizes on some level Lola's "royalty": in Round One he calls her the "house princess" ("Holla, holla, Lolalola, die Hausprinzessin") and in Round Two he lectures her on the virtues of queens. It is their third encounter that reveals the film's deeper fairy tale status.

Lola, having just missed her father, stands in front of the entrance of the bank, shouting "Scheiße, Scheiße!" ("Shit, shit!") when Schuster, his fairy tale role as doorkeeper now altered, steps outside for a smoke break. "So you made it at last, darling," he says ("Da bist du ja endlich, Schatz"), which Lola finds not at all amusing. Schuster himself seems surprised by what he says. Something isn't right here. Lola's gaze rivets him. Does he recognize that this is the third time Lola has come to the bank, that somehow his world has been split three-ways? Do he and Lola realize that it's she who's controlling the game? How has he become a part of Lola's game of repetition with variations? Or is it possible that he recalls, if only faintly, his role in the film's prologue as the kicker of the soccer ball, the one who puts the (non-diegetic) ball into play? And if so, what are the ontological consequences of his recognition? Lola runs on, but Schuster stands still, and we hear the loud pounding of his heart.

Does Lola possess the power to affect the heart rate of the characters in her game? Certainly from run to run she has gained in knowledge and power. No need in this final round to ask the old woman for the time (she's not even in this round); instead, Lola enters the casino and twice wills the ball (the second time with the help of her scream) to land on 20. Then she climbs into the back of the ambulance and there on the stretcher is Schuster having his heart massaged, but to no effect. "What do you want here?" the attendant asks, and Lola says, "I belong to him" ("Ich gehör zu ihm"). Then she holds his hand and brings his heart beat back to normal.

No question now that we're headed for a fairy tale happy ending. Lola has the money to save Manni, and Manni, as it turns out, has found his missing money (with the help of the fairy tale-like blind woman outside the phone booth whose "gaze" he follows and sees the bum passing by on a bicycle) and returned it to Ronnie. As they hold hands, Manni asks Lola what's in the bag. Lola smiles. The End. But we should note the film's final dialectical move: ENDE enters from frame right and the credits roll from top down.

Life, Run Lola Run implies, is like a game of roulette; the player is not the spinner; nonetheless, the player can affect the outcome. Or as Tykwer puts it: "The world is a stack of domino stones, and we are one of them. . . . On the other hand, the most important statement is the end: Not everything is predetermined" (117).

Finally, fairy tales begin "Es war einmal," "Once upon a time," and this omniscient point of view is echoed in Run Lola Run's opening. What is the world of the film's prologue? Not exactly a diegetic one; more the open ground before the actual story begins, when a voice speaks to us, not the author, but a storyteller outside the limitations of time. Characters mill around and from them the camera selects those who will be in the game. And as it does, a voice says:

Man, probably the most

enigmatic species on our planet. A mystery of open questions. Who are we? Where

do we come from? Where are we going? How do we know what we believe we know?

Why do we believe anything? Innumerable questions searching for an answer, an

answer that will generate a new question,[end of p.39] and the next answer the

next question, and so on, and so on. But in the end, isn't it always the same

question, and always the same answer?

Hans Paetsch, the actor who delivers this voiceover, "was God" for Tykwer as a child, "because he always knew everything. Run Lola Run is a game in which we claim the power, so to speak, to change bits and pieces and to influence fate as well. Something that usually only gods can do. Hans Paetsch, with his soft, warm voice, brings irony into the construct and in this way expresses that Run Lola Run is a fairy tale as well" (130). German viewers of all ages recognize in Paetsch's voice the omniscient narrator of fairy tales. With this reflexive gesture ("influx of mind"), Tykwer begins his film's philosophical project of disrupting determinism, and for the next 81 minutes, like Lola, we, too, if we work at it, can become the player rather than the played.

Tom Whalen has taught film

studies at the University of Stuttgart, Germany, and

Notes

I wish to thank Susan Bernofsky for her comments on this essay and Annette Wiesner for her suggestions, insights, and close readings, which made my work not only better but possible.

1. Throughout this essay I rely on the original German of the film, at times complemented by the shooting script. Credit for the translations, with minor emendations by me, is due to Annette Wiesner.

2. Annette Wiesner connected these four shots for me.

Works

Cited

Dawson, Jan. Wim Wenders. Tr. Carla Wartenberg.

Hegel, G.W.F. Hegel: The Essential Writings. Ed.

Frederick G. Weiss.

Kolker, Robert

Phillip and Peter Beicken. The Films of

Wim Wenders: Cinema as Vision and Desire.

Nabokov,

Quinn, Daniel and

Tom Whalen. A Newcomer's Guide to the

Afterlife: On the Other Side Known Commonly as "The Little Book."

Tykwer, Tom. Lola rennt. Ed. Michael Toteberg.

[end of p.40]

COPYRIGHT 2000 University of California

Press

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group